Did the English wine revolution start in, er . . . Essex?

November 29, 2017One man and his vineyard

October 26, 2017PAUL OLDING has a bit of an advantage over the rest of us when it comes to planting a vineyard. He has already written a much praised book on the subject, “The Urban Vineyard” based on a tiny one of his own on an allotment in Lewisham, south London. Now, in fulfilment of a long held dream, he is going rural with Wildwood, a lovely one-acre vineyard on a sunny south/south-eastern facing hillside off a bridle path in vine-friendly East Sussex.

Having endured tortuous procedures to get planning permission both for the vines and a shed he then suffered the freak late frost after bud burst that hit vineyards throughout the UK inflicting wholesale damage on the crop. But those and numerous other problems are in the past. Now he and his family can now look with satisfaction at a thoroughly professional vineyard with no noticeable side effects from the frost.

It was a very un-Brexity multinational effort: vines and wires from Germany, end posts from Belgium, the larger cabin from Latvia, the smaller one from Slovenia, a tractor insured in Wales and a toilet from Ireland installed by Romanians. Skilled Romanians also put in all the posts (and planted the vines) as is common in English and Welsh vineyards. But the wine will be unashamedly English.

When? Paul, who is 44, believes in letting the roots settle and is planning only a small harvest in 2018 using two bunches from the stronger vines with a full harvest planned for 2019. The plot was purchased in 2014 but it took 18 months of preparation doing such tasks as reducing the acidity of the soil by spreading lime.

He is growing (highly popular) Bacchus, Regent and two varietals of Pinot Noir. This is clearly a fun thing for him and he is not expecting to make much of a profit and especially not if the huge cost of land is factored in. There are no plans to give up the day job as a TV producer/director (including some of Brian Cox’s films). With an acre of vines and several more acres of ancient woodland attached slithering down to a happy stream he has already created his own dream world. But he will still have to pray for good weather.

I am hoping to keep an occasional eye on Paul’s progress. You can buy his book at http://theurbanvineyard.co.uk/.

His website is wildwoodvineyard.co.uk

At last – a plaque for the man who proved that the English made “Champagne” first

May 26, 2017

IT COULDN’T have been better timed. This week a long-awaited plaque was unveiled in Winchcombe, Gloucestershire at the birthplace of Christopher Merrett. It was Merrett who in a paper to the Royal Society in 1662 recorded that what came to be known as the méthode champenoise – ie secondary fermentation in the bottle – was actually invented by wine coopers in England decades before it was attempted by Dom Perignon. Most French people still, erroneously, believe that it was all due to the Dom, not the Pom.

It was a memorable occasion – with lovely wines supplied by Paulton Hill, which introduced us to its first sparkling, and Lovell’s vineyard which markets the fine Elgar range and is the nearest vineyard to the birthplace of Christopher Merrett. It was well timed because the English and Welsh wine revival seems to have entered a new period of growth. It is not just that a million new vines are expected to be planted this year – most of them for sparkling – but our still wines are starting to win serious prizes.

A fascinating example is the northernmost vineyard in North Wales, Conwy, (@conwyvineyard) which I visited two years ago and was told that New Zealand legend Kevin Judd, the man behind Cloudy Bay, on a visit to promote his new venture had noticed some grapes growing on a hillside as the train came into Llandudno station. He commented that it was a great position for a vineyard and he would love to come back for a tasting. Well, if he does he will find that Conwy, owned by a delightful couple Colin and Charlotte Bennett has just won one of only two silver medals awarded for UK still wines at this month’s International Wine Challenge. The other silver was awarded to LondonCru, which operates London’s first winery for centuries. Oh, and Conwy also won a bronze for its Solaris. Not bad for a vineyard of barely an acre in an area of Wales where most people would be amazed to find grapes growing at all.

The plaque at Winchcombe was unveiled by Mike Read, best known as a DJ but who has written 36 books, many on historical subjects, and is a founder of the British Plaque Trust. Mike boldly entered the controversy about what to call the indigenous sparkling wine discovered by Merret. He suggested English Royal which has a lovely prestigious ring about it – with hidden notes about Charles II who espoused the Royal Society – but I am not sure how it would go down in North Wales! But it is a lot better than the headline a bright sub editor wrote on an editorial I wrote about Christopher Merret’s discovery 20 years ago in the Guardian. It was “Champagne Pom” I was much moved by the warm reception a packed church gave to me for my talk on Merrett – including this poem . .

In praise of Christopher Merrett

(from my fifth poetry book LondonMyLondon published on Kindle this morning!)

What makes Champagne go full throttle,

Is secondary fermentation in a bottle.

This is an invention without which,

Sparkling wine would be mere kitsch.

And who made this spectacular advance?

Why, in folk law, a monk, Dom Perignon of France.

But wait: hear Christopher Merret’s scientific view,

Which he wrote in sixteen hundred and sixty two

Without any mock Gallic piety,

He told the newly formed Royal Society,

He’d discovered this oenological advance

That let wine ferment in bottles first,

That were strong enough not to burst.

T’was Britain’s gift to an ungrateful France

Decades before they gave sparkling a glance

It created that country’s strongest brand.

So, let’s raise a glass in our hand,

To a great man’s invention from afar

And drink to the Methode not Champenoise

But What should have been called Merrettoise.

So, let all by their merrets be

Judged – that the whole world can see

That however we may be thought insane,

We gave the French for free – Champagne.

Will still white wines be the next big thing for Britain?

July 27, 2016THE AMAZING resurgence of UK vineyards in recent years has overwhelmingly been the story of sparkling wines which have been so festooned with gold medals that even French champagne makers have woken up to it. But is the same success about to happen to our still white wines which have languished in the shadows for so long? You could definitely draw this conclusion from the recent English and Welsh Wine of the Year competition where an astonishing 20 out of 32 gold medals awarded went to white wines of which no less than 11 were made from the appropriately named Bacchus grape (after the god of wine) which is emerging as the UK’s still wine of choice for consumers. Several other non-Bacchus wines also struck gold including chardonnays from Chapel Down’s Kits Coty vineyard and from the long-established New Hall in Essex.

This competition was blind tasted by Masters of Wine judged, it is claimed, to international standards which means that there ought to be no national bias. The trouble is that at the more recent Decanter blind tasting – which includes wines from everywhere and not just England and Wales – there were no golds for Bacchus or indeed any other still wines from the UK though there were three silvers (plus a few more for other still whites). This is par for the course for international competitions. So what on earth is going on? There are various explanations. It could be that domestic Bacchus producers did not enter in sufficient numbers for Decanter. Maybe there a subconscious patriotic preference for home producers by the judges. Not at all unlikely. Or , just possibly, the success of Bacchus in domestic competitions is a lead indicator of what is to come in international blind tastings. After all, our sparkling wines were hailed at home long before they started winning prizes in international competitions. Or, perish the thought, wine tasting is a much more random operation that its participants like to admit.

Either way, there are lessons here. Maybe the new vineyards being planted here which are overwhelmingly of the three varieties that make up classic Champagne wines – Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier – should look to plant more for still wines. Of course, if the market changes, it is easy to produce still white from Chardonnay vines and still red from Pinot Noir, which is gradually improving in quality in this country. But Bacchus, which is a cross between hardy Germanic varieties Mullar-Thurgau and Sylvaner x Riesling, is clearly emerging as the cheer leader for UK wines with a name to conjure with.

Bacchus wines are not cheap being mainly priced around the £14 mark though at the time of writing you could get a Brightwell Bacchus at £9.99 from Waitrose and a 2014 from Chapel Down for £11.50 from the Wine Society. Waitrose is the best place to look for English and Welsh wines if you are not buying from a vineyard, not least because they occasionally have special offers with cuts of 25% or more and they have over a 100 English and Welsh wines on offer. The choosey Wine Society (lifetime membership £40) has a much more limited but high quality list including a couple (non Bacchus) at under £8. Both organisations have free delivery if you buy by the case.

So it looks as though Bacchus will be a premium priced wine like our sparkling wines. If you haven’t got the economies of scale of overseas producers it makes sense to sell on quality. The name Bacchus can be used by anyone but the way things are going it could establish itself as a distinctively branded English still wine. That would be something worth waiting for.

London vineyards – a weekend break

June 19, 2016

LONDON has long been an international centre for wine but none of the growing or production has happened in the capital for centuries. Now things are changing, albeit on a small scale. The latest news is that the admirable Vagabond Wines, where you can buy up to 100 wines by the glass (which would be attractive to punters wanting to try out English or Welsh wines) is planning to build a winery in London to make wine from grapes grown in this country. This means that London could soon have two wineries of its own following the pioneering efforts of London Cru in Earls Court.

Yesterday (Saturday) I added another London vineyard to my experiences when I visited one I was previously unaware of in Morden (See photo, above) at the southern end of the Northern Line in the middle of suburbia. It is quite sizeable for an urban vineyard with over 300 vines but there is no way you would know it was there as you can’t see it from the street and the owners understandably intend to keep it that way and asked me not to reveal its location.

From here they have been making white, red and rosé wines since the mid 1990s on reclaimed allotments from well tried cool-climate varietals such as Triomphe, Dornfelder and Dunkelfelder which they turn into wine at their own well-equipped micro winery. What they don’t drink they distribute to friends and relatives. They kindly gave me a bottle of white which I look forward to sampling.The terrain is not text book ideal – soft clay soil on ground that slopes the wrong way – but it seems to work. Even when you are in the house it is a bit of a maze to find the exact location but well worth the unique experience of viewing suburbia from a secret vineyard. If anyone knows of any other vineyards in London however small please contact me on victor.keegan@gmail.com.

From Morden it was only a few stops on the Northern Line to Tooting Bec station where I somehow managed to find my way to the vibrant Furzedown Festival to collect my annual allocation of four bottles of Chateau Tooting which makes wine from grapes grown in gardens and allotments across the Capital. You are allocated bottles in proportion to the weight of grapes you put in. This year – a rosé made into wine by the highly regarded Halfpenny Green vineyard in Staffordshire – was sweeter than last year’s excellent offering but very drinkable even though I don’t have a sweet tooth. Chateau Tooting makes north of 600 bottles and is the second largest wine priducer in London.They seemed to be doing a roaring trade at their stall yesterday.

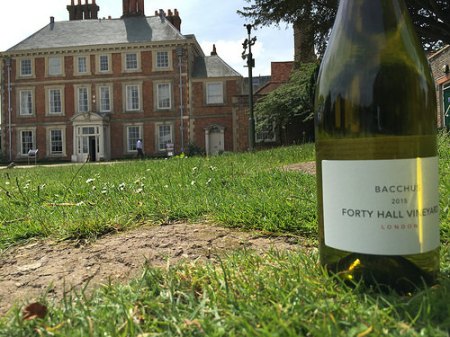

This morning – yes, this is definitely London wine collection weekend – I trekked to Enfield in North London to the 10 acre Forty Hall (photo, left) which is emerging as the most exciting vineyard in London for a very long time. I bought a few bottles of its Bacchus, which has been well received by early imbibers plus an Ortega. Its second sparkling wine will be released later in the year probably only for patrons until production gets fully underway. Forty Hall is an organic vineyard run by volunteers, some of whom have social problems which are greatly helped by the therapeutic value of vineyard involvement. I felt a bit better just by strolling around. The wine is made for them by Davenports, the highly respected Sussex winery, and the combination of the two organisations looks like a highly encouraging blend.

Chateau Tooting’s stall at the Furzedown Festival)

How bad are your tastebuds?

March 28, 2016I RECENTLY attended a fascinating lecture on the chemistry of tastebuds at University College London (Department of Chemistry). During the course of it the lecturer, Tony Milanowski from Plumpton College, handed around four cups of clear liquids and asked us to pass them around after writing down a) whether we smelled anything at all and b) if we did what sort of aroma it was.

The first two had no smell at all and were obviously water (who was he trying to fool?) while the other two had distinct perfumes which I noted down. At the end of the talk he revealed that he had intended to pass around a fifth cup but as it was only water he decided not to bother.

Oops! After decades of drinking wine I was unable to detect half of the smells of the liquids. It was scant consolation that most of the rest of the audience seemed to be in the same boat and the student next to me only managed one. It turned out that the last one should have tasted of asparagus to which some people have what is termed a “genetically determined specific hypersensitivity ” to it. And others don’t sense it at all.

The fact is that the vast majority of people who drink regularly do not have sophisticated taste buds and many of those who do actually fail in blind tastings.

There is no such thing as an “objective” taste in a glass of wine or any other liquid. What you are tasting is not what I am tasting. Taste depends on genetics (the multitude of receptors and sensors in your mouth and up your nose), but also on mood, temperature, place, the company you keep, expectations and even the label. That bottle of rosé that tasted so heavenly on a beach in the south of France but was quite mundane at home is not to be blamed. It wasn’t that it didn’t travel it was because the environment in which you drunk it did not travel.

If you are given a glass of Chateau LaTour in a posh restaurant it will taste different to the same wine served up anonymously in a plastic cup. All of this is highly relevant to the appreciation of English and Welsh wine. If you have it built into you that the wine is no good – as so many people in the UK still believe about their own wines – then it is difficult to detach the psychology of expectations from how you taste it.

You are not alone. In America Robert Hodgson, an academic and a winemaker has carried out a detailed analysis of blind tastings in California over a number of years by acknowledged experts. The results astonished him. Some 90% of judges didn’t have any real consistency often giving quite different marks to the same wines. About 10% of the judges were ‘quite good” – until, that is, he compared them with the following year when they couldn’t maintain their performances. When he tracked 4,000 wines across 13 competitions he found that virtually all of those that got a gold medal in one competition got no award at all elsewhere. His conclusion? The probability of getting a gold medal matches almost exactly what you’d expect from a completely random process. Ouch.

Of course, even if judges were completely consistent about a wine it doesn’t mean you will like it because your tastebuds and receptors may be completely different. Experts make a great play of detecting notes of gooseberry, raspberry, nettles and even pencil shavings in a wine though they would rapidly recoil from a wine made from those constituents. A 2011 Chateau Tooting, made from grapes of unknown parentage grown in back gardens and allotments in London, was recently given a mark of 88% in a blind tasting by wine expert Jamie Goode. In the end there is no alternative but to follow your own nose while being aware of all the flummery about wine.

All of which ought to be good for the future of UK wines as they start to break through the barrier of psychological resistance. It is already happening with sparkling wines (though how they would fare under a Hodgson analysis is an interesting point). But there is still a widespread belief that English and Welsh wines can’t be much good simply because they are English or Welsh. There is all to play for.

This is an edited version of an article in the current issue of UKvine magazine .

Christmas lunch – two wines from London

December 24, 2015THIS YEAR we are going to have two wines from London (yes, London, England) and one from Wales for our Christmas lunch. If this doesn’t get us into the Guinness Book of Records nothing will. As an aperitif it will be Forty Hall sparkling, claimed to be London’s first sparkling wine for centuries. I managed to get a bottle because as a patron I was entitled to just one as output is being restricted in early years in order to boost future growth. I was going to keep it for a while as it is rather young for a sparkling but then I was offered the opportunity, again as a patron, to buy another two bottles – so that made it worth the risk of opening one for Christmas. Forty Hall is London’s largest vineyard for a very long time and maybe ever. It is an inspired community-run 10-acre project at Enfield whose grapes are turned into wine by Will Davenport, one of England’s most respected winemakers.Can’t wait.

For the turkey there is a choice. For some reason – and I am not sure where I went wrong – the rest of the family always prefers white to red. So there will be a bottle of LDN Cru, a Bacchus made at what is claimed to be London’s first urban winery in West Brompton using grapes from the family-owned Sandhurst vineyards in Kent. Purists may argue whether this is really a London wine as the grapes are grown outside the capital. But vineyards such as Chapel Down and Camel Valley always brand under their own labels even when the grapes come from Essex or wherever. For me it’s London and I look forward to a glass.

Finally, another first – a domestic red with the turkey. I am very interested in the way Pinot Noir – the grape behind Burgundy – is developing in the UK as a premium product and have already been very impressed with Gusbourne and Hush Heath Pinots this year. I also have bottles of Sharpham and Three Choirs gathering age. But this time I have decided on one from Ancre Hill in Monmouth. Their sparkling whites have been festooned with gold medals but they also have a long-term interest in producing top quality Pinot Noir in Wales. Well, that was the difficult bit. Choosing. Now it is all over bar the drinking. Happy Christmas to all.

Britain at its most picturesque – the Wye Valley wine trail

June 8, 2015

THE WYE VALLEY has a strong claim to be the cradle of the tourism industry in Britain. When Continental wars deprived monied people of the Grand Tour in Europe they perforce turned homewards and the Wye Tour from Ross-on-Wye to Chepstow – passing Goodrich Castle and Tintern Abbey – became the trip to make for them and for poets like Wordsworth and Thomas Gray not to mention painters such as Turner.

It is almost the last place you would think of today as a vineyard destination. That is because we define our vineyards by county or pre- defined regions and can’t easily cope with a river haven like the Wye Valley which transcends countries – Wales and England – as well as counties (Gloucestershire, Monmouthshire and Herefordshire). But today it has a strong claim to be a vineyard destination as well.

Travelling up the Wye from Chepstow the first vineyard you come to is Parva Farm on the left of the river (open all year) stunningly situated up a steep slope in Tintern overlooking the river and, if you reach high enough, the Abbey. Its wines have won a stack of silver and bronze medals. Marks and Spencer recently asked for as much of its Bacchus as they could spare.

A few miles up river at Monmouth you can visit Ancre Hill Estate (April to end September) a biodynamic vineyard which burst on to the scene two years ago when its 2008 (Seyval) white was voted the best sparkling wine in the world at the Bollicine del Mondo in Verona beating off competition from established champagnes. This was an astonishing achievement for a new Welsh vineyard which even my Welsh friends have difficulty in believing. On a sunny day eating a lunch of their local cheeses, vines stretching out before you, with one of their lovely sparkling or still wines (Pinot Noir, Chardonnay etc) is a great joy.

Further upstream at Coughton, near Ross-on-Wye, on the site of a Roman vineyard, is newcomer Castle Brook whose delicious Chinn-Chinn 2009, made with classic champagne grapes, recently won a gold medal and was voted the best sparkling white in the whole of the South-West Vineyard Association’s area beating off the likes of Camel Valley in Cornwall and Furleigh in Dorset. Castle Brook is owned by the Chinn family, probably the biggest asparagus growers in the country. It is open by appointment but wine can be purchased online.

Further north, less than ten miles from the Wye with a good restaurant and accommodation is the highly regarded Three Choirs whose 80 acres produce fine prize-winning wines, including gold. The vineyard also makes wine for dozens of other vineyards. If you take into account the whole vineyard experience – including the quality of wine, the setting, the food and the atmosphere, this one is up with the very best.

Strawberry Hill vineyard, so close to Three Choirs that you could almost use it as a spittoon, is one of the most unusual vineyards anywhere and one of my favourites. It makes good wines (some stocked by Waitrose) partly from over an acre under glass enabling it to grow Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon not normally possible in England.

It claims to be the only vineyard in the world growing commercially under glass, which no one has yet contested. As if that isn’t enough, it has rows of flourishing banana trees – growing outside! – as well.

There are plenty of other vineyards in The Wye Valley (depending on where you draw the boundaries) including a new 3.5 acre one at Wythall in the grounds of a stunning Tudor mansion, Lullham, the wonderful Broadfield Court, also Coddington, now under happy new ownership, Sparchall and a micro vineyard The Beeches at Upton Bishop. This is by no means a complete list. If all these can’t generate a vineyard trail I don’t know what will. If Wordsworth were alive today, I wonder if he would have written about Wines a few miles above Tintern Abbey rather than his celebrated “Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey” .Either way Galileo’s description of wine as sunlight held together by water has a unique resonance in the Wye Valley.

Was the White House in Washington named after this vineyard in Wales?

March 4, 2015IT IS a curious fact that the great English wine revival was really started in Wales by a Scot. The Earl of Bute established two vineyards in Glamorgan at Castell Coch and Swanbridge. From the mid 1870s until the 1914/18 war – when supplies of sugar needed for fermentation dried up – he and his son ran the only commercial vineyard in the UK. This ended the Dark Ages of UK wine production and proved to subsequent UK pioneers that if white and red wines could be successfully made in South Wales then the prospects must be good for other parts of the UK.The Bute vineyard at Castell Coch is now a miniature golf course (below) but the revival of Welsh wine is now in full swing and gaining international attention.

The flagship is the newcomer Ancre Hill Estate of Monmouth, run by the engaging Morris family, which broke the English monopoly of gold medals when its 2008 white was voted the best sparkling wine in the world – against competition from Champagnes – at the prestigious Bollicine del Mondo blind tasting in Italy. Since then it has won a further clutch of gold and silver medals and is in the middle of an expansion which involves new acreage at a nearby farm and a state-of-the art biodynamic winery.

But Ancre Hill is merely one of a flourishing network of vineyards in Wales which are starting to make their mark in the wider world. The most interesting newbie, is Jabajak. (picture above) (Don’t reach for your Welsh dictionary – it is an anagram of the initials of its founders). At the moment it is an anomaly; a vineyard without wine. This is because they dumped last year’s crop as not up to the standard they are seeking so their first wines won’t be ready until May. But the rest of the infrastructure is in place including rooms, 3.5 acres of vines, a carp pond and a restaurant already producing first class food including scallops which were among the best I have tasted and delicious Welsh lamb.

As if this isn’t enough they have a potentially killer selling point. It is in their lease that they must keep the main house painted white, a condition laid down when it was a farm owned by David Adams who subsequently emigrated to America and whose grandson (John Adams) and great grandson (John Quincy Adams) both became Presidents of the United States. It was during John Adams’ presidency that the President’s abode was first referred to as the White House even though this was long before it was actually coloured white. Locals in this part of Wales believe it was called the White House because of stories handed down by the Adams family that the white house in Wales was where the decisions were made. Whether you think this is a load of jabajak or not doesn’t matter: if people start believing it over the water, they may have to build a new airport here to meet demand.

Seventeen miles west of Jabajak surrounded by the Pembrokeshire National Park is the most curious vineyard in Wales, Cwm Deri (“Valley Oak”) Estate (picture, left). Not only does it have four of its own shops (one at the vineyard and others in Cardiff, Bridgend and Tenby) which is unusual for a vineyard but it also sells grape wines mixed with other fruit wines as well as conventional ones. I sampled a wild damson with medium dry rosé in the conservatory restaurant overlooking the vines which tasted like I imagine a damson Kir would.

There are a number of other interesting Welsh vineyards which I have covered in previous blogs including the lovely Sugarloaf Vineyards near Abergavenny, the recently created White Castle vineyard at Llanvetherine, the surprisingly good Parva nestling above the tourist haven of Tintern and the doyen of them all Glyndwr which has been making steadily improving wines at a blissfully secluded six acres at Llanblethian since 1982 much of which goes to Waitrose.

Among other well established vineyards Llanerch stands out as providing the best overall package with very nice food and drink with a restaurant, outside tables, shop and a local walk.

Another one to look out for is Llaethliw (“colour of milk”) in Dylan Thomas country near Aberaeron where Plumpton-trained Jac Evans, aged 24 bides his time between working on an oil rig near Aberdeen and tending his parents’ 7 acres of vines with another 15 acres to be planted over the next two years. Last year 1,600 bottles were sold out before Christmas. This year he hopes for 6,000. Wales is on the move.

@Britishwino @Jabajak @ancrehillestate @cwmderi

Did the English invent sparkling wine from their own vineyards?

November 16, 2014 IT IS NOW well accepted, that the English invented what came to be known as the Méthode Champenoise thanks to Tom Stevenson’s amazing discovery of a paper presented to the Royal Society in 1662 by Christopher Merret of Gloucestershire. Stevenson’s assumption was that the English were using their sparkling wine technology to make imported still French wines fizzy.This couldn’t have happened in France because their bottles were so fragile they would explode during a secondary fermentation (and, anyway, they didn’t have corks). The English had a lead of at least 20 years in sparkling technology.

IT IS NOW well accepted, that the English invented what came to be known as the Méthode Champenoise thanks to Tom Stevenson’s amazing discovery of a paper presented to the Royal Society in 1662 by Christopher Merret of Gloucestershire. Stevenson’s assumption was that the English were using their sparkling wine technology to make imported still French wines fizzy.This couldn’t have happened in France because their bottles were so fragile they would explode during a secondary fermentation (and, anyway, they didn’t have corks). The English had a lead of at least 20 years in sparkling technology.

But could it be that the Brits were also producing fizz from still wine made from grapes grown in England? If so, this would mean that the current boom in home produced sparkling wine is merely a revival of something we pioneered from our own vineyards.

I have just been reading – thanks to Google scanning it – William Hughes 1665 classic, The Compleat Vineyard which strongly suggests that the Brits had been making sparkling wine out of home-grown grapes for quite a while.

Hughes admits that most of our wines were imported but he also points to

vineyards in Essex, in the west of England, and Kent, which “produce great store of excellent good wine”. Indeed the entire book is about growing grapes in England.

Among various suggestions, he says: “If the wine be not brisk, how shall we make it without the addition of Sugar, Vinegar,Vi?riol & to sparkle or rather bubble in the Glass”.

He has another suggestion for English wine: “Suppose you have a piece of Wine which naturally is too sharp for your drinking, you may draw it out into bottles, and in each bottle put a spoonful or two of refined sugar, and so set them in sand in a Cellar, and let them stand a considerable time before you drink it, and you will find it a pleasant and good Wine”

All this was contained in The Compleat Vineyard” which is a do-it-yourself manual about growing grapes in Britain. My edition was published in 1665. It must have been several years in the writing and printing and he must have been describing what were quite common practices. Isn’t it high time we celebrated this achievement more vocally to assist the success of our sparkling revival? There was an interesting conversation on Twitter recently suggesting that April 23 (St George’s Day and Shakespeare’s birthday) should be designated English Sparkling Wine Day. It would be a shame if it bit the dust.

@BritishWino You can get these occasional posts directly by filling in the email slot on the right of the screen

Posted by shakespearesmonkey

Posted by shakespearesmonkey